How do we live? This is the fundamental question. Our lives are a cascade of objects and events, joy and sorrow, all conducted in front of the backdrop of a world which just continues on as usual no matter what is going on in our own lives. What do we make of if all? Is it ever possible to say of our lives “this is my life, I want no other?”

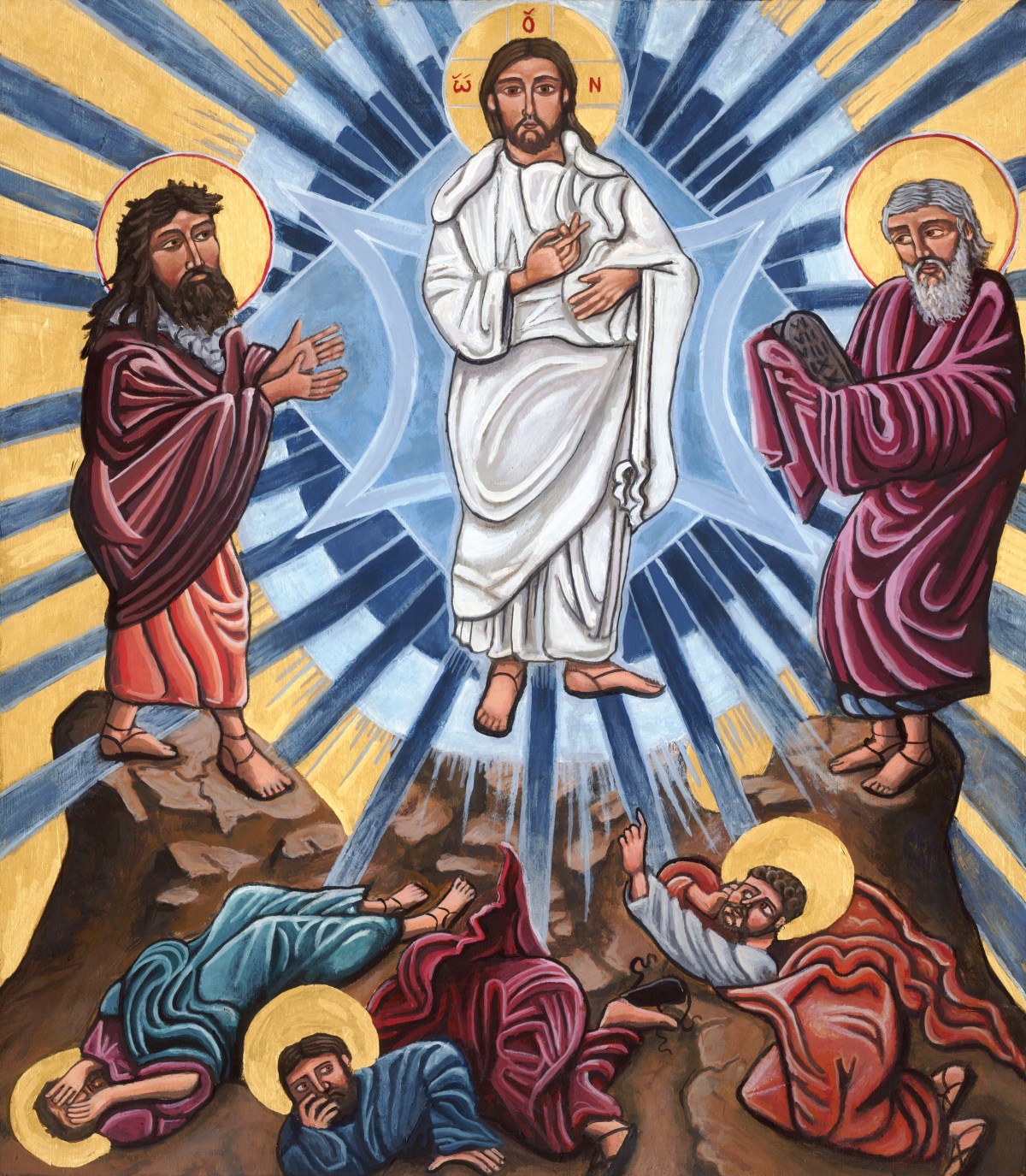

Today we are confronted with one of the stranger stories from Scripture, with Jesus transfigured, his face shining like Moses’ did when he met with God – but bringing a gift from God more powerful than commandments written on tablets of stone.

Amongst all the strangeness, there is something powerful and important going on. Something which exactly speaks to our deep, existential need. What does it mean for us to hear God say that Jesus is “my Son, the Beloved”, with whom God is “well pleased”, and that we should “listen to him”?

Does the story of the Transfiguration have something to say to point us towards the life that is truly worth living?

Let’s start with the elephant in the room. I suspect a lot of us find the “mystical woo-woo” side of the story hard to take. We bring our perfectly sensible questions to the story: how did Peter know that it was Elijah and Moses standing there? What does it actually look like for someone’s clothes to be “bright as light”? Who wrote this down, and why did Jesus tell the disciples not to talk about it until after he was raised from the dead? We worry a lot about what an independent observer would have seen.

It sounds like a vision, and that makes us feel uncomfortable. What we like is a nice, publicly observable, event where we can all agree on what happened. Ideally one which we can repeat on demand, in a controlled environment.

What we really respect is Science with a capital S. In fact, I think it is not too big a leap to say that we worship it. I’ll come back to the idea of worshipping science in a moment, but for now let’s just note that Science is the thing by which everything else is valued and measured and put to the test, and generally found wanting, because whatever is not science is second rate. We think Science is Truth – and we say things like “believe the science” when we want to make our point as emphatically as we can.

But is it really Science, in the sense of “knowledge about the world” that we value most highly? I wonder if it is really the power that science gives us to control the world. After all, at its best, Science takes discoveries about nature, and uses them improve people’s lives, and there are many examples of that. Jonas Salk and the Polio vaccine, for instance. Or Barry Marshall, who proved that peptic ulcers were mostly caused by bacteria, not by stress or spicy food. At its worst – well, I don’t suppose we have seen its worst yet, but let me just gesture at Hiroshima and the Holocaust and perhaps some of the more alarming predictions about AI.

This is going to seem like a bit of a strange juxtaposition, but I would like to engage you in a quick Bible Quiz. How many trees of power were there in the Garden of Eden? Two. The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and the Tree of Life.

And, of course, Eve and Adam ate the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Our first reaction is: so what? Surely it is better to know the difference between good and evil, if only so that you know what to do and what to avoid? It sounds a like they swallowed a book of moral instruction.

But, in fact, the idea of the “knowledge of good and evil” points to power. After all, the Serpent’s promise was that it would enable them to become like God. It is the power to know good and evil from intimate experience. It is the knowledge of the power to do good or evil to someone – from the person standing right in front of you up to a whole nation.

But, as we noted earlier, there were two trees of power in the Garden, not just one. The other tree, the one which Eve and Adam did not eat from, was the Tree of Life. The tree of being nourished by the “eternal sort of life” that John’s Gospel talks about. The life that comes from knowing God.

So, to get back to my thoughts about the real nature of our love of science, we essentially like to pretend to ourselves that the “fruit of the tree of knowledge” is about a disinterested search for truth, but in fact it is at least as much about this knowledge understood as power.

That’s the story behind the story of all the awful stories from the Book of Genesis onwards, right up to the terrible stories in our headlines today. We humans eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, but we do not eat from the Tree of Life.

And the thing about eating from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is that we really, really, really don’t want God muscling in. Adam and Eve heard God coming, taking the cool of the evening, and promptly hid amongst the undergrowth.

We, too, hear God coming, and want to hide – not literally in the undergrowth as a rule, but we hide in our theories, in our knowledge of science, in the story of universal power and control that we tell ourselves. The story that we can build a modern-day Tower of Babel, a civilisation so powerful that it can replace God, and at last we could be truly safe.

Today’s story of the Transfiguration strikes us as bad news, or at least ambivalent news, because, if it literally happened like the writers said, it means that we don’t have universal power and control. And that, we really cannot stand. That our story is not actually the central one about the universe. Because God shows up, and we want to make for the undergrowth.

It’s a deep desire of ours, to make the world predictable and controllable, and ultimately to make it our servant. We want to remove risk from our lives, and the problem with stories like this is that it shows God interrupting the nice, predictable flow of events.

Science and technology have been comparatively good at providing a comfortable standard of living for those of us in the West – certainly better than the alternatives – but it turns out that a comfortable standard of living is not really enough.

Or, as someone sensible once said, one cannot live by bread alone.

And he wasn’t talking about the importance of eating one’s vegetables.

To make it worse, it seems increasingly likely that the basic bargain of our world is struggling to cope. It can be easy to gesture at “cost of living” pressures and sort of shrug, but the world where the fundamental bargain is that we will get richer and richer, and that a rising tide of wealth will float all boats, seems to be fracturing.

This seems to be how the world seems to a lot of young people – that they have been sold a pup, a story that, if they work hard and do well at school and get into university they will get a good job and be able to have the sort of life their parents had, and now it is all unravelling. What seemed to my generation like a trap to be avoided – a corporate job and a car and a house in the suburbs with 2.2 kids – seems like a fantasy to a lot of young people.

So if you get lucky, the world keeps its side of the bargain, and you get rich enough to not to need to worry where your next meal is coming from, we still find ourselves preoccupied by what we don’t have – always someone richer, always someone more successful always someone who seems like they have it all together.

And then, if you aren’t so lucky, you feel locked out of the world and the basic bargain of our civilisation – buckle down, work hard, and you’ll get have a safe, secure, prosperous life – is not being kept.

When all we have is the material world, it is very, very hard to say “this is my life, I want none other.” When the key thing about like is to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, we end up in a world defined by power, a world of winners and losers, where even the winners are restless and not content at soul.

A world in which we desperately need to eat from the tree of life. But how?

In this world constrained by the immanent frame of science, where we are in love with our own power, and where we do not eat from the fruit of the tree of life, the eruption of God into our world can feel very threatening. But it can also break us out of the narrow horizons of a world without God that secularism has created.

But it is, in fact, good news, because God is not content to leave us with only one sort of fruit. We hear God call Jesus “my son, the beloved, in whom I am well pleased” and that changes everything about our world.

The Transfiguration of Jesus is a world-shaking event, and it is right that the liturgical colour for the day is white, because it is an event, second only to the Resurrection, that shows us who Jesus is and what Jesus means.

In fact, it is so profound that calling it an “event” undersells it. The Transfiguration, like all of the signs performed by Jesus, reveals to us what God is always doing everywhere. It draws the curtain aside for a brief moment to reveal to us that Jesus is the new Moses, the successor to, and fulfilment of, the Prophets. The image of the unknowable God, the one who reveals God to us.

This is Good News because it breaks us out of the world where the only goods are those generated by science, and especially by the application of science and power that we call technology. All of us, whether we feel like we are winning or losing at life, need to eat from the tree of life, and the Transfiguration of Jesus points to the basic truth about the universe that the “one thing necessary” is to be swept up into what God is doing, through Jesus Christ, and through the ongoing work of the Holy Spirit. To be swept up into the life of God.

Jesus was talking with Moses and Elijah – named, specific, individuals. God works through individual people. God loves individual people, and offers Godself to individuals, rather than nations and classes. Obviously, we should be doing what Jesus says – after all, God says “listen to him.” But, more than that, is that God offers us the chance to be swept up into what God is always doing in the world. Which, ultimately, means to be swept up into the life of God, the ultimate source of meaning.

God is always offering us the sort of life where we can say “this is my life, I want no other.” God is always offering us redemption and transformation. The God who loves each of us, individually and by name, offers us, through Jesus and the power of the Holy Spirit, nothing less than life with God, both now and forever.

To the holy, blessed and glorious Trinity,

three persons and one God,

be all glory and praise, dominion and power,

now and forever.

Amen.

A sermon on Matthew 17:1-9, preached at Church of All Nations Carlton on 15/2/26